Picture this: millions are dead from extreme heat, coastal cities have been swallowed by the sea, and waves of desperate migrants are fleeing devastation, fueling a surge in military conflict and xenophobic fascism. Given current levels of atmospheric carbon, these outcomes may be inevitable.

What’s more, climate change could eventually lead to our extinction.

That’s the silver lining.

Climate antihumanists contend that humans have been such poor stewards of the natural world that we should exit the stage and allow plants and animals to re-inherit the Earth. Most aren’t actively trying to raise p(doom), but they welcome human extinction as a just punishment for our many crimes against nature.

Some antihumanists are more committed to the cause. They’re not comic book villains plotting mass genocide, but they would like to help humanity fade into oblivion. (Children of Men isn’t dystopian; it’s aspirational.) Some, such as those in the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement, refuse to have children and implore others to do the same. Some pin their hopes on a race of benevolent AI that will supplant us and gently shepherd our species into hospice care. To be clear, none cheer for a gory extinction marked by protracted suffering—just a peaceful fade to black (or green).

As Adam Kirsch explains in a slim book titled The Revolt Against Humanity, climate antihumanism unites two very different kinds of radicals: environmentalists who revere a pristine, prehuman idyll and technofuturists who dream of replacing meat with machines.

At first glance, climate antihumanism may seem fringe and outlandish. The zealots in Kirsch’s book deserve journalistic curiosity more than serious rebuttal. But the view is strangely popular in progressive circles.

Last year, I wrote a New York Times op-ed arguing that progressives should care about population decline. An alarming number of readers were comfortable with humanity’s decline—many even wanted us to zero out. Calling humans “a virus,” they declared allegiance to “team extinction.”

I mused about these comments to my wife, knowing that she would take their side. In her view, humanity enjoys no moral privilege over other species, and we can only hope that the planet is able to repair itself in our absence. (We have two kids. She’s not a very committed antihumanist.)

Truthfully, I wasn’t surprised by the progressives who leapt into the comments to cheer for our demise. Like other questionable moral and political doctrines—such as illiberalism about free speech or opposition to nuclear power—climate antihumanism has been left-washed. But how?

Many progressives experience apocalyptic dread and historical guilt. They seek moral clarity, which antihumanism delivers. And because it signals wise pessimism about the climate crisis and profound concern for the environment, antihumanism has become a badge of moral seriousness. This helps explain why it persists despite such obvious and devastating flaws.

And what are those flaws? Let me start from the beginning.

The universe was dark for billions of years until the glow of consciousness emerged on one planet—and nowhere else, as far as we know. Eventually, beings evolved who experienced joy, made each other laugh, and fell in love. Extinguishing this light would be an incomparable tragedy.

To see this more clearly, consider the loss of particular groups and cultures, the disappearance of their rich and diverse ways of life. Some Indigenous groups in North America and beyond have succumbed to the pressures of colonialism, their traditions erased. By welcoming human extinction, antihumanists also welcome such tragedies.

Humans are certainly not the only life forms that matter intrinsically, but we do possess higher moral status. We harbor richer inner lives, forge deeper relationships, and pursue long-term projects imbued with meaning.

None of this is to deny that humans drastically underrate the value of the living world—nor to excuse our carnage. Every year, we condemn nearly 100 billion animals to brutal abuse and grisly deaths on factory farms. We’ve ravaged natural ecosystems, wiping out thousands of unique and irreplaceable species—we may be causing the sixth mass extinction in Earth’s four-billion-year history.

So yes: animal lives matter. (The jury’s still out on plants.)

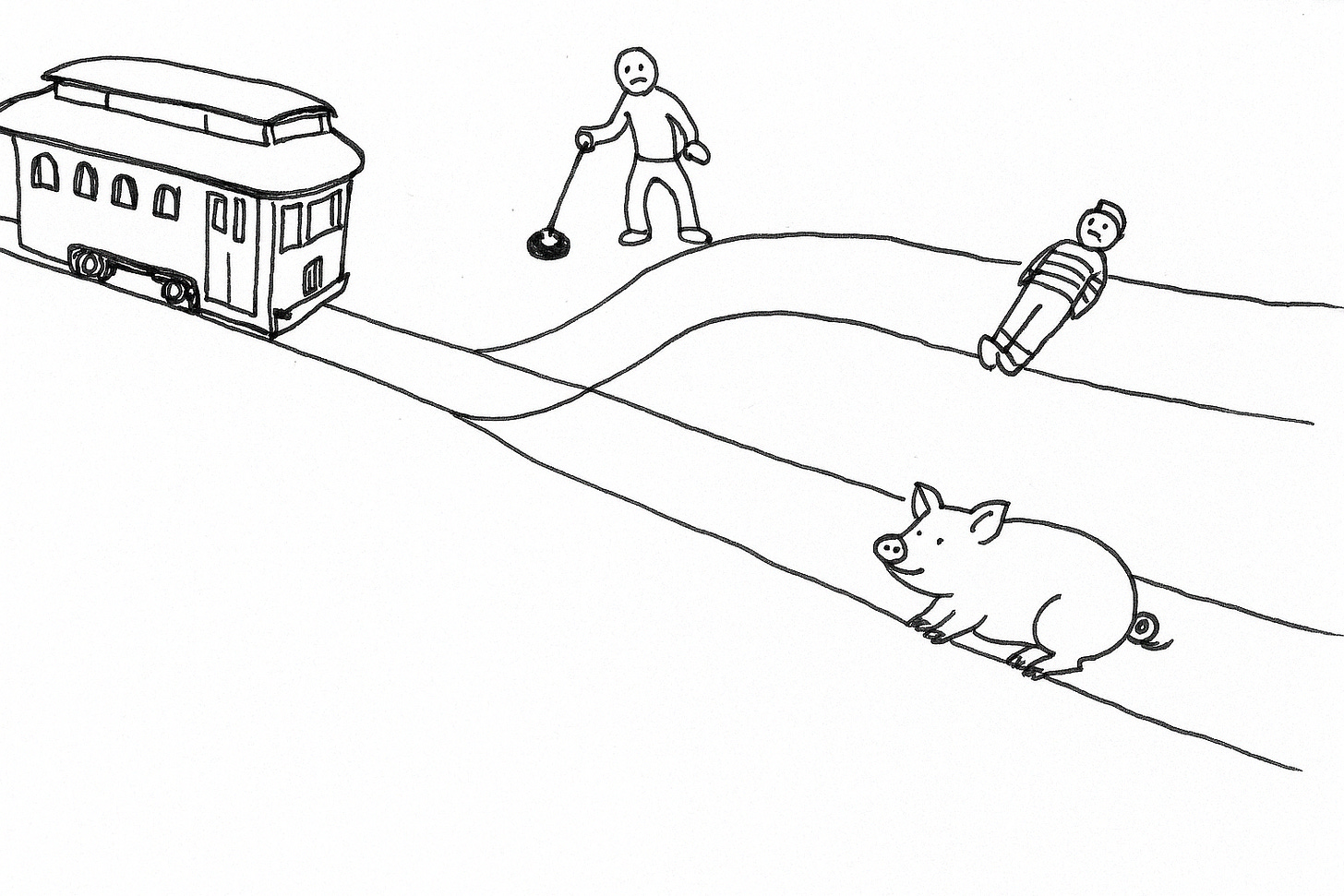

Yet human lives matter more. Faced with the choice of saving either a human or an animal, the answer is clear. Ethics is replete with hard dilemmas. This isn’t one.

“We’ll disappear eventually anyway, right? So why worry about it?” Granted, our species isn’t immortal, but that’s no reason to embrace extinction—just as individual mortality gives a young person no reason to embrace premature death.

Some progressives acknowledge the unique value of human life but defend team extinction by distinguishing living humans who matter from the possible future humans who don’t. We should grieve existing groups who disappear—but not those unborn. Preempting their existence is no loss.

To be sure, some temporal discounting is inevitable, even if only as a concession to our limited power. We shouldn’t care as much about the next millennium as we do about next Tuesday.

Yet on the timescale of social progress a hard distinction between current humans and future humans is almost meaningless. Every great moral project spans generations.

Think of the eradication of deadly diseases or the civil rights movement or the construction of democratic societies. None fit into a single lifetime. Fundamentally, social progress depends on the eradication of hardship and oppression. And realistically, if we want to help the poor, people of color, and other marginalized groups, our plans must be measured in centuries.

Progressives often have a remarkably bleak view of the future, one that begins to look absurd when measured against the relentless progress achieved over the last few hundred years. True, much of that progress has been for us humans at nature’s expense. But when our ingenuity and efforts have focused on the environment, the results have been bracing. We’ve slashed industrial pollution, restored the ozone layer, and ignited a revolution in solar energy. We should give ourselves a chance to achieve one more long-term progressive goal—to build a sustainable planet where all life flourishes. Why quit now?

If we care about life on Earth—including plants and animals—quitting is not an option. Their salvation depends on us. The planet’s climate is self-correcting only on a timescale of tens of thousands of years. There is no alternative but to fix our mistakes.

Antihumanists want humanity to die out as penance for our sins, but that punishment would be extreme, grossly disproportionate to our crimes. Moreover, the innocent would perish along with the guilty. We should, rather, save our victims from what would await them in our absence. Instead of accepting retribution, we should pursue restorative justice.

Making amends means not just cutting emissions and investing in renewables. It also demands reducing environmental damage that is often overshadowed by climate change—other forms of pollution, biodiversity loss, habitat destruction, and industrial animal farming.

Many of us are understandably anxious about the prospect of climate upheaval. We reject the rampant anthropocentrism that underlies ruthless exploitation of the planet, affirming instead that every form of life has intrinsic value.

But we should still choose team humanity over team extinction.

Ensuring the continuation of our species doesn’t commit us to human chauvinism. We should consider our own interests while balancing them against the interests of the rest of the planet. The challenges are vast, but humanity deserves a chance.

I'm really curious about the psychology of this mindset. It's just fascinating to me that the prevalent progressive stance on environmentalism is pro human extinction. People who (I believe authentically) care the most about marginalized groups are the first to send entire human race down the drain. My initial thought is that it's an attempt at signaling a kind of moral erudition and magnanimity, but it still doesn't make sense to me.

I also have the feeling that this is the secular remnants of a religious mindset: belief in a sort of teleology in nature. If only humans left it alone, the planet would thrive and reach its predestined goal. Someone was looking after us by providing us with this bountiful earth, and we just chose to ruin it for our greed -- for this, we must suffer. We should cease our existence for things to return to their natural order, just as it was intended. Yet, of course, there is no greater intention behind any of this. And any trade off should give proper weight to human flourishing.

Great post! Though - if you'll excuse the nitpick - I don't think our limited power implies that "We shouldn’t care as much about the next millennium as we do about next Tuesday."

Distinguish fundamental concerns vs instrumental focus. We shouldn't bother *focusing* much attention on problems that we can't change. But that's not the same as *not caring* about the problem.

As a test case: suppose an evil demon credibly offered to give you a lollipop in exchange for his getting to torture people millennia hence. Temporal discounting (given a sufficiently distant time) implies that you should accept the demon's deal: far distant people *aren't worth caring about*, on that view. But that's insane. Obviously those far future people matter, and given an unexpected opportunity to affect their interests, you should not discount them. It's just that it isn't usually worth *attending* to far future people, insofar as we doubt our ability to reliably affect their interests.

It isn't plausible that the demon's deal should change our values or *what we care about*. But it's perfectly reasonable for an unexpected option to change *what we should attend to*, "activating" or making salient certain values that were previously "dormant" for reasons of practical irrelevance.