Getting Schooled

What I learned studying philosophy and what I’m still learning

Duncan MacIntosh was voted “Best Professor” in The Coast’s Best of Halifax competition in 2005 and again in 2007. In an interview with the campus newspaper, he shrugged it off: “It’s nice and so on, but it’s the same way they vote for falafels.”

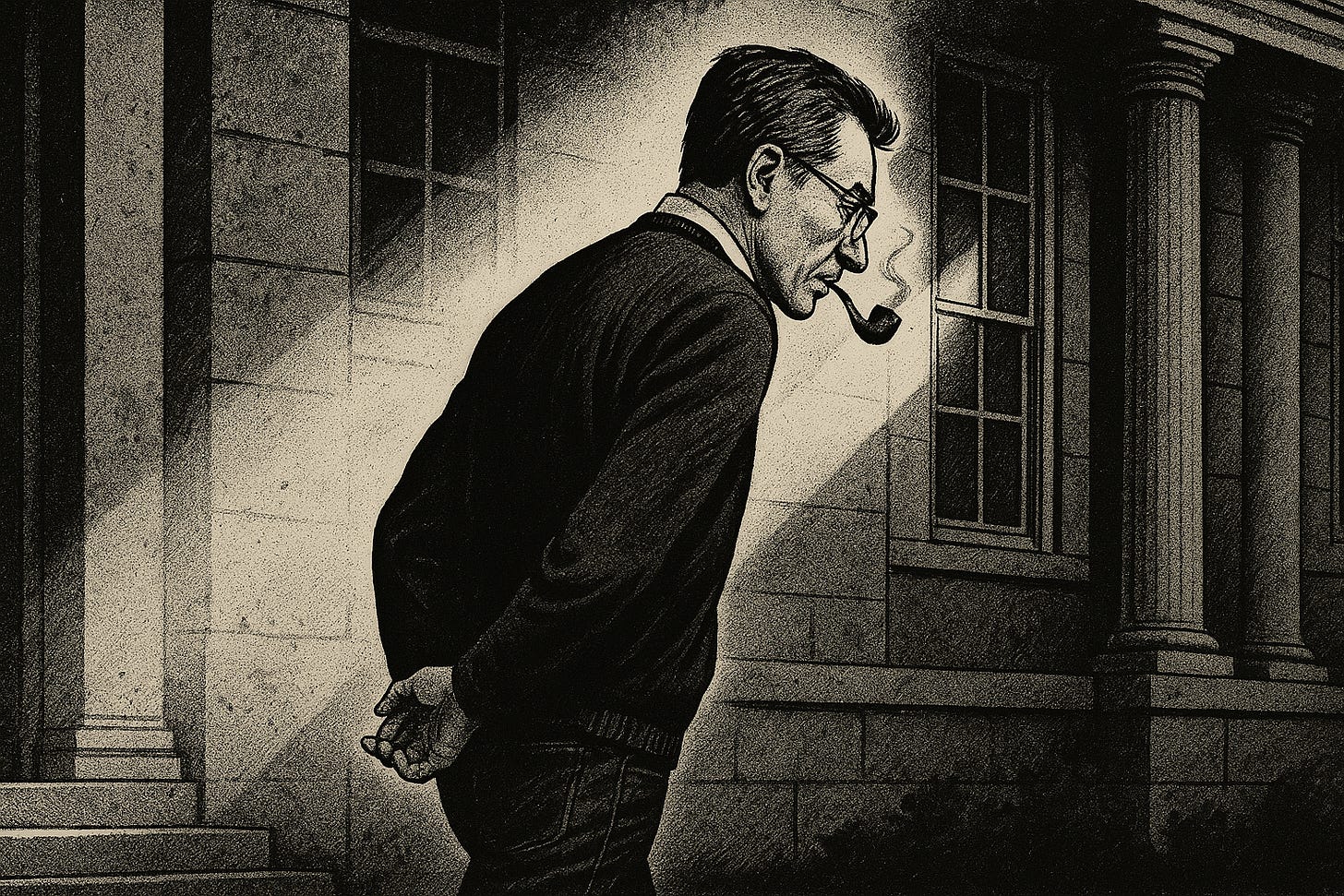

Duncan had black hair, graying at the temples. He always wore a dark sweater or blazer over a white collared shirt. Outside the philosophy department, you’d see him smoking a pipe, hands clasped behind his back, leaning slightly forward. In the classroom, he was electric—a charismatic lecturer who paced the room and never lost his audience or failed to make us laugh. My friends and I would leave his classes buzzing, arguments spilling into the hallway. We dubbed ourselves the “Duncamaniacs.”

Students seem to choose their majors based on preexisting interests, but this is an illusion. Their interests are shaped by the professors who inspire them—and whose approval they seek. I still intended to earn a science degree and pursue a PhD in evolutionary biology until another Duncamaniac persuaded me to attend the first meeting of Duncan’s seminar. Long story short, I now find myself in the lucrative and high-powered field of academic philosophy.

One of the most exciting things about Duncan’s seminars was that he taught his own work-in-progress. In one, he gave us his manuscript on personal identity. Duncan was known for his view that it’s rational to revise your ultimate preferences to satisfy your original ones. In his manuscript, Duncan built on this idea, arguing that identity can endure through radical psychological change so long as the change is rational. (Too much rationality? Or exactly enough? That’s how we philosophers like it.) It was thrilling to read the book and engage directly with the author, especially because Duncan greeted criticism so enthusiastically; nothing seemed to please him as much as a tough objection. I learned, as another mentor would say, that in philosophy we show respect by criticizing one another’s ideas. Refraining from criticism signifies that your interlocutor is unworthy of it.

I took this lesson with me when I began teaching my own seminars, assigning draft chapters from my book manuscript on evolution and moral progress. It was a total flop—the vibes were awful. Students pulled their punches; I felt sheepish defending my views. Only later did I realize why. To become a good teacher, as with all self-improvement, one must follow the Socratic dictum: know thyself. And as much as I admire Duncan’s teaching style, I’m different. I prefer to “teach the controversy” and remain neutral about where I stand, at least nominally. To each their own, but for me this posture is vital for giving students the freedom to discover what they think for themselves.

In a typical class, Duncan would spend the first twenty or thirty minutes delivering a crystal-clear lecture, distilling the central arguments from the reading. Then he’d do something unusual: he’d go around the room, pointing at each student in turn and inviting them to ask a question or raise an objection. (You were allowed to pass.) I’d choose my seat strategically, far enough from the front to refine my question as other students spoke—but not so far back that class might end before my turn came. This teaching practice may not sound particularly innovative, but it gave everyone an opportunity to participate. Too shy to raise your hand? If Duncan pointed, you might as well say your piece.

Another signature habit of Duncan’s was to lavishly and shamelessly compliment each of us on how interesting or brilliant our question was (even when it wasn’t). He’d then “restate” the question, rationally reconstructing his way to a much better version than the original (sometimes to an entirely different question). As I now tell my graduate student teaching assistants, it’s hard to overdo this. People enjoy praise; the wish to be well-thought-of usually overcomes self-doubt.

I’m not as effusive as Duncan, but I want my students to gain self-confidence, sometimes more than they’ve strictly earned, because that’s conducive to actually earning it. When a student raises an objection, I praise them and do a little rational reconstruction—but then I ask what others think. I want students to engage one another, not just me.

The Coast never ran an official poll, but Duncan was also far and away “Best Interlocutor” at our department’s weekly colloquia. For those who don’t know, the standard colloquium format gives the speaker an hour to present and the audience an hour to grill them. (Too much Q&A? Exactly enough! That’s how we like it.) Duncan’s questions were famously incisive. When his name was called, everyone swiveled in their seats, eager to be past the undercards and on to the main event. First, Duncan would summarize the speaker’s central argument far more clearly and concisely than the speaker had. This was the opening jab, sometimes provoking embarrassment for the speaker and for the audience on his or her behalf. If you couldn’t express your ideas half as well as Duncan, you probably didn’t fully understand them. Then came the uppercut: a devastating objection to the heart of the talk, from which there could be no recovery. The speaker attempted to respond, futilely, and Duncan might press back, gently, but when the speaker didn’t get it, Duncan relented. What distinguished the good philosophers was that they at least registered how hard the blow had landed; the poor ones had no clue. QED. TKO.

For years, I modeled my questions on Duncan’s. Anyone who knew me in grad school would tell you that my questions were excellent, though they might also say (correctly) that I was a show-off. Early on, I forced myself to ask a question at every talk, sometimes hurling my arm into the air against my will. That’s how I conquered crippling anxiety about public speaking. (Early in college, I so badly wanted to avoid the final oral presentation in one course that I skipped it and accepted a B-.) This was also how I learned to be a better philosopher. After asking a question and finding that I hadn’t been sufficiently clear or thorough—allowing myself to be misinterpreted or leaving an avenue of escape—I’d castigate myself and rehearse how I should have articulated the question. Next time, my question was better though still not perfect. More rumination.

These days, I no longer try to ask questions like Duncan. Not because I’ve soured on adversarial debate. Quite the opposite: I think it’s a shame that some philosophers now conduct Q&As like little lovefests. Can someone raise a goddamn objection? Socratic dialogue is how we refine our ideas, the whetstone that sharpens our steel. There’s nothing wrong with being critical, even severely, so long as you aren’t cruel or moralizing. No, I gave up my old aggressive style because I realized my motive was corrosive—I wanted to gain social status by winning. (How much of my admiration was based on Duncan’s social status rather than just his intellect?) Watching other philosophers, I learned that there’s more than one way to ask productive questions. Yet there is one lesson from Duncan that I’ve held on to. When a speaker doesn’t get it, you don’t keep pressing. Show mercy.

I was a student in four of Duncan’s courses in the early to mid-aughts. I also graded for his intro course—attending his lectures even though he said I didn’t have to—and wrote my Honors thesis under his supervision. (My thesis was on the “new problem of induction,” and one section was devoted to criticizing Duncan’s solution.) As it happens, this was during the tail end of a golden period in the Dalhousie philosophy department. Faculty were deeply engaged with one another. Colloquia were held every week except for holidays, about forty-five times a year—basically unheard of elsewhere. And everyone was expected to attend: faculty, graduate students, undergrads. It didn’t matter whether the talk was in an unfamiliar area; this was a chance to learn. As I was graduating, though, younger faculty were hired who didn’t subscribe to this ethos. They had busy lives—family and friends and travel commitments. Attendance slipped. The crowd at the grad pub afterward thinned. Some even asked their question and snuck off before the Q&A ended! The departmental culture never disappeared—they still hold weekly colloquia to this day—but it faded. What they once had was special: a philosophical community that was intellectually bracing and personally enriching, perhaps essential to a good life of the mind. And it was like family—you didn’t choose them but they were yours.

Nowadays, I sympathize with those younger, truant faculty. Colloquia and other talks are scheduled in the late afternoon and early evening, and there are only so many days I want to miss dinner with my two small kids—only so many times I want to impose on my wife. What’s more, while I used to be an “all-rounder”—interested in almost any area of philosophy—I’m not anymore. If it isn’t related to contemporary politics or culture, I struggle to maintain interest. Duncan, too, once a scholar’s scholar, later turned to less esoteric topics, such as autonomous weapons and foreign influence in democratic processes, joining a think tank at Penn. A radical shift; no doubt he had his reasons.

Post-PhD, it’s hard to maintain an intellectual community. I have a few philosophy friends in town who I talk shop with, but that doesn’t hold a candle to the community that Duncan and others helped create. I doubt that Substack can fill that gap—that reading and commenting and reposting can ever be a substitute for those heady, vibrant discussions. Maybe the best way to satisfy my ends would be to adopt new ones: to care about a wider range of philosophical ideas and value a community I haven’t chosen.

What I’ve done instead is create a philosophy lab—now consisting of a few colleagues plus some of our current and former students. Every other week, one of us presents their latest project. The ethos of the lab is to build up each other’s ideas rather than tear them down. We raise tough objections, yes, but we also help each other devise replies. Could this grow into something like the old culture at my alma mater? Are we building a community that is personally enriching and capable of molding young philosophical minds? I’m learning.

There is no place like Dal in the early aughts. We were so lucky!!!

Pressure to publish is another reason why strong discursive communities dwindle. Especially for young faculty, there is often a genuine choice: Do I spend my intellectual energy trying to understand and formulate good questions about this talk in a field that has nothing to do with my research? Or do I try to save that energy and focus on developing my own ideas? Sure, there are some “cross-training” benefits, but at the end of the day, what my job and my community really rewards isn’t the incisive Socratic generalist who publishes little but the narrow focused specialist who has many prestigious publications. Some can do both, and if you can, that’s great. But many can’t.