It Gets Better (But Only Sometimes)

Why gay progress accelerated while trans progress stalled

In mid-century America, LGBTQ+ people lived in the shadows. Those who dared to be openly gay or trans were disowned by their families, cast out of their communities, and fired from their jobs. Then a moral revolution began—but progress was uneven.

While anti-gay prejudice steadily eroded, anti-trans prejudice proved more resilient. Homosexuality stopped being classified as a medical disorder; same-sex marriage became legal. Yet the trans movement did not enjoy corresponding success. Trans adults still lack a right to gender-affirming health care. In about half of US states, gender identity remains unprotected under hate crime legislation. Trans people waited longer to serve openly in the military, and in 2025, they were banned once again.

This lag might seem inevitable. But why?

It’s not a law of nature that gay progress must outpace trans progress. In some places, gay people face harsher persecution. Many indigenous communities in North America embrace “two-spirit” identities while forbidding men from coupling. In Iran, gender-affirming surgery is not just legal but government-subsidized, while gay men face the death penalty. There is a possible world in which trans progress accelerated in the US while gay progress stalled.

Maybe the American pattern is pure happenstance? One theory holds that the HIV/AIDS crisis sparked sympathy for gay people—the disease itself but also the obscenely cruel political response—and that this chance snowball triggered an avalanche. Indeed, researchers find that homophobic prejudice declined in US states with higher rates of HIV/AIDS. Had the epidemic never occurred, gay progress would have stalled too.

No—the lag was not an accident. There are deeper reasons why gay progress outpaced trans progress in the US. Some are demographic; others offer bitter political lessons.

First we have to understand why gay progress was so rapid, especially compared to other forms of liberation.

In the 1960s and 70s, as counterculture flourished and young people flocked to cities, gay neighborhoods emerged, especially in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Washington, DC. In these havens, gay identities were not just tolerated but celebrated. You could be openly gay without stigma. You could find friendship and community. You could fall in love.

More and more gay people were drawn to these neighborhoods and came out of the closet—not just within their newfound communities but also to friends and family members back home, people who loved, respected, and trusted them. Through these personal connections, straight Americans began to witness how harmful homophobia was and to see through its cruel falsehoods, such as the lie that gay people are unfit to be parents.

Straight people encountered a living, breathing refutation of anti-gay ideology. They realized: if it’s OK for my child/friend/cousin to be gay, then it must be OK for everyone. Against entrenched and incipient bigotry, love won—not always, but more and more often.

Gay communities continued to thrive—first in real life and then online. More and more gay people came out of the closet, changing the hearts and minds of straight people in their lives. Eventually, gay public figures came out and transformed their admirers. Wider cultural acceptance followed, bringing reforms to social institutions. Laws changed, yes, but families, schools, and firms also became more inclusive. Activists started winning consistently because the public had become sympathetic.

These changes made it easier for more gay people to come out of the closet, which changed the hearts and minds of those who knew them, which led to wider cultural acceptance and more institutional reform, which made it still easier to live openly... As Richmond Campbell and I contend in A Better Ape, moral progress often emerges from this kind of virtuous circle, as psychological and systemic change feed each other and overwhelm inevitable backlash.

If this account is right, homophobia dissolved more quickly than certain other forms of bigotry—like racism—for two main reasons. One is that sexual orientation is a hidden trait. You can get to know and love someone before discovering that they’re gay—your guard against acceptance lowered. The other is that gay people are more or less randomly distributed across the population. The contrast with race could not be more stark: racial identities are acutely visible and do not transcend kinship. In America, racial groups are highly segregated.

This explains why gay progress was so fast. Does it also explain why trans progress lagged behind? Like sexual orientation, gender identity is also a hidden trait (before socially transitioning certainly but often after) and more or less randomly distributed. So why the disparity?

One difference is that variation in gender identity is less common, by nearly an order of magnitude: roughly speaking, 8-10% of Americans are gay or bisexual, while only 1% of Americans are trans. (Historically anyway. It’s unclear how stable these numbers are.) This translated into less manpower to fuel the trans movement, but it also meant fewer cis people had opportunities to undergo moral transformations through personal connections with trans people.

Another difference is that while gay people seek romantic relationships with other gay people, trans people don’t share this essential imperative. So there wasn’t the same drive to build trans neighborhoods that fostered greater openness. Plus, some trans people prefer—reasonably—to pass as cis rather than be open about their identity, if possible. Ultimately, without a strong drive to affiliate and live openly, trans people were less likely to come out to family and friends and help them overcome prejudice.

The difference still holds. According to one 2023 survey, 84% of Americans know someone who is gay, lesbian, or bisexual, while only 36% know someone who is trans. Former vice-president Dick Cheney discovered that his daughter was gay and broke with the Republican party’s line on same-sex marriage—decades before Joe Biden’s relationship with a trans politician from his home state fostered his endorsement of trans rights.

Some disagree with this explanation. They contend that trans progress lagged for political reasons: LGBTQ+ movements, captured by their most privileged members, prioritized sexual orientation over gender identity, as when politicians dropped gender identity from federal anti-discrimination bills. But this explanation puts the cart before the horse. Such decisions—whether prudent or craven—were made because lawmakers and activists recognized that the public is more sympathetic to gay rights than trans rights.

Others point to cultural forces. In the late 1990s, major TV shows—Ellen and Will & Grace—featured main characters who were openly gay. Trans characters didn’t break through until the mid-2010s. Similarly, schools began teaching students about sexual orientation a decade or so before daring to broach gender identity. Again, though, the cart doesn’t drag the horse. These cultural forces are real, yet they took hold only because the public had become more receptive to gay people than trans people. But for that, TV executives and school boards would have made different choices.

Fundamentally: there were fewer trans people, with less motivation to come out—which meant less influence on the cis people in their personal lives and the wider world. A virtuous circle could not build momentum.

But that’s not the whole story.

In an essay about the interplay between culture and politics,

identifies another reason that trans progress lagged behind gay progress: more onerous “asks.”Fundamentally, gay people asked to be left alone—to live their lives as they wanted. Many freedom-loving Americans could understand why they’d prefer that the state didn’t police their bedrooms or marriages. The idea that same-sex marriage would somehow damage straight relationships was always weak on its face. Meanwhile, the social and legal acceptability of homosexuality went hand-in-hand with wider sex liberalism—the loosening of taboos around contraception, premarital sex, “indecent” sex acts, and the like.

But, Heath suggests, “the ‘ask’ involved in trans acceptance differs radically.” Consider the politics of pronouns. For many in Gen-X and older, it’s difficult to systematically adjust pronoun usage for people they’ve already coded as a particular sex or for those whose appearance does not correspond (conventionally) to their gender identity.

Even more onerous, as Heath and many others have pointed out, is the demand that cis people reconceptualize their own sense of self. The gay movement said, “I’m just like you.” The trans movement says, “You’re not who you think you are.”

Correctly or not, cis people have naturalized their gender identity, treating it as a biological given. But to avoid “transphobia,” you must see your own gender as entirely unrelated to your sex and instead as a social performance. You’re not simply a man or a woman; you’re a cis man or a cis woman. Your sexual orientation, even, must be defined in terms of your gender, not your sex—on pain of bigotry. But also, your sex is (supposedly) a social construction too; it was only provisionally “assigned” at birth, so you must stop thinking of your sex as given too.

To be clear, the point is not that any of these asks are unreasonable, nor even that they are less reasonable than corresponding asks from the gay movement. The point is simply that they are more onerous.

I’m not so sure about this story.

Heath goes on to identify another reason trans progress has stalled—that the underlying politics has been toxic:

“The expectation seems to have been that it would be unnecessary to present arguments in support of these demands, or to respond to common objections…. A small unpopular minority…persuaded itself that intolerance could be a useful weapon in its political arsenal. [This was a result of] their early success in achieving outsized influence within certain elite institutions, including media corporations, and then vastly overestimating the effectiveness of these cultural institutions at achieving social change.”

Yet this makes me wonder whether trans “asks” aren’t inherently any more onerous than gay “asks,” or not by very much, and whether the primary difference is rather that the trans movement arrived 30 years later, during the Great Awokening, which led to a surge of intellectual tribalism on the left, and was accompanied by more strident and ultimately less effective political tactics.

Fundamentally, it seems to me, trans people are asking for the same thing as gay people: let us be. Gay people seek the legal and social acceptance of their relationships; trans people seek the legal and social acceptance of living in accord with their gender identity. Without stigma or discrimination. For the most part, that request is easy to grant.

The gay movement said, “I’m hardly any different from you, I’m just attracted to people of the same sex.” The trans movement says, “I’m hardly any different from you, I’m just in the wrong body.” At least, that’s what many trans people say, unless they’re under the influence of academic theory. When Chase Strangio says “a penis is not a male body part. It’s just an unusual body part for a woman,” he is asking cis people to radically alter their self-conception. The problem here is common to the last decade of progressive politics: ideologue capture.

In fact, contrary to what is often assumed, cis people don’t need to accept that their gender has no connection to their biological traits in order to treat trans women as women, trans men as men. Trans people are in the wrong bodies after all. Sex and gender are linked.

This doesn’t mean traditional notions of gender are untroubled, but neither are traditional notions of sexual orientation. In particular, straight people had to reconceive their sexuality as one possibility among many rather than as a neutral default. Similarly, while the trans politics of pronouns can be delicate, so can the gay politics of “partner” and the like.

Granted, not all trans people feel that they are in the wrong body or that they were “born that way.” But trans progress does not require ordinary people to internalize academic theories of gender that fully accommodate the diversity of trans experience. Nor is it necessary to learn neo-pronouns (ze/zir), to replace “breastfeeding” with “chestfeeding” or “mother” with “birthing parent,” to believe that gender-affirming medical care should be free of all “gatekeeping,” or to support schoolteachers enabling children to socially transition without parental consent. These “asks” are onerous, yes, but they aren’t justified.

It’s true that social acceptance of trans people creates an administrative and financial burden—such as the infrastructure for supporting changes to legal identity or the expansion of insurance coverage. But that’s on a par with the social acceptance of gay people and the new families they created. Consider the infrastructure for same-sex adoption or new policies covering spousal benefits. Besides, these aren’t really public asks—not demands for ordinary people to do anything in their everyday lives.

This perspective on the recent past can help us understand what’s happening now.

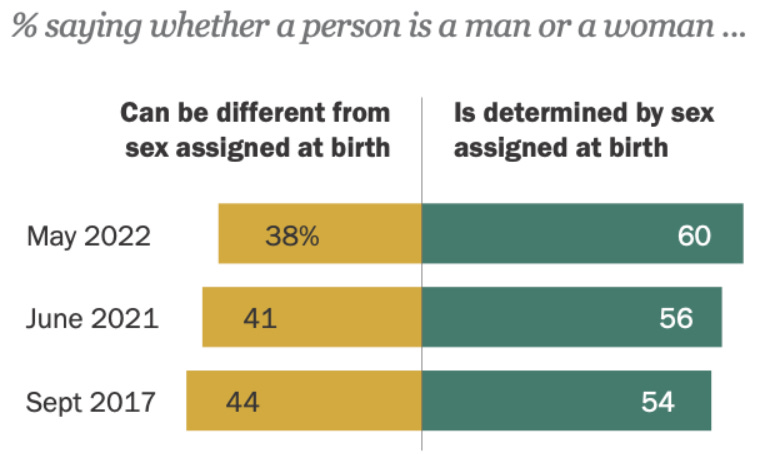

For the last few years, the US has been engulfed in a brutal backlash. Where trans progress once stalled, it’s now reversing. Hundreds of anti-trans bills have been passed by state legislatures. More and more Americans believe that whether someone is a man or a woman is determined by their sex at birth.

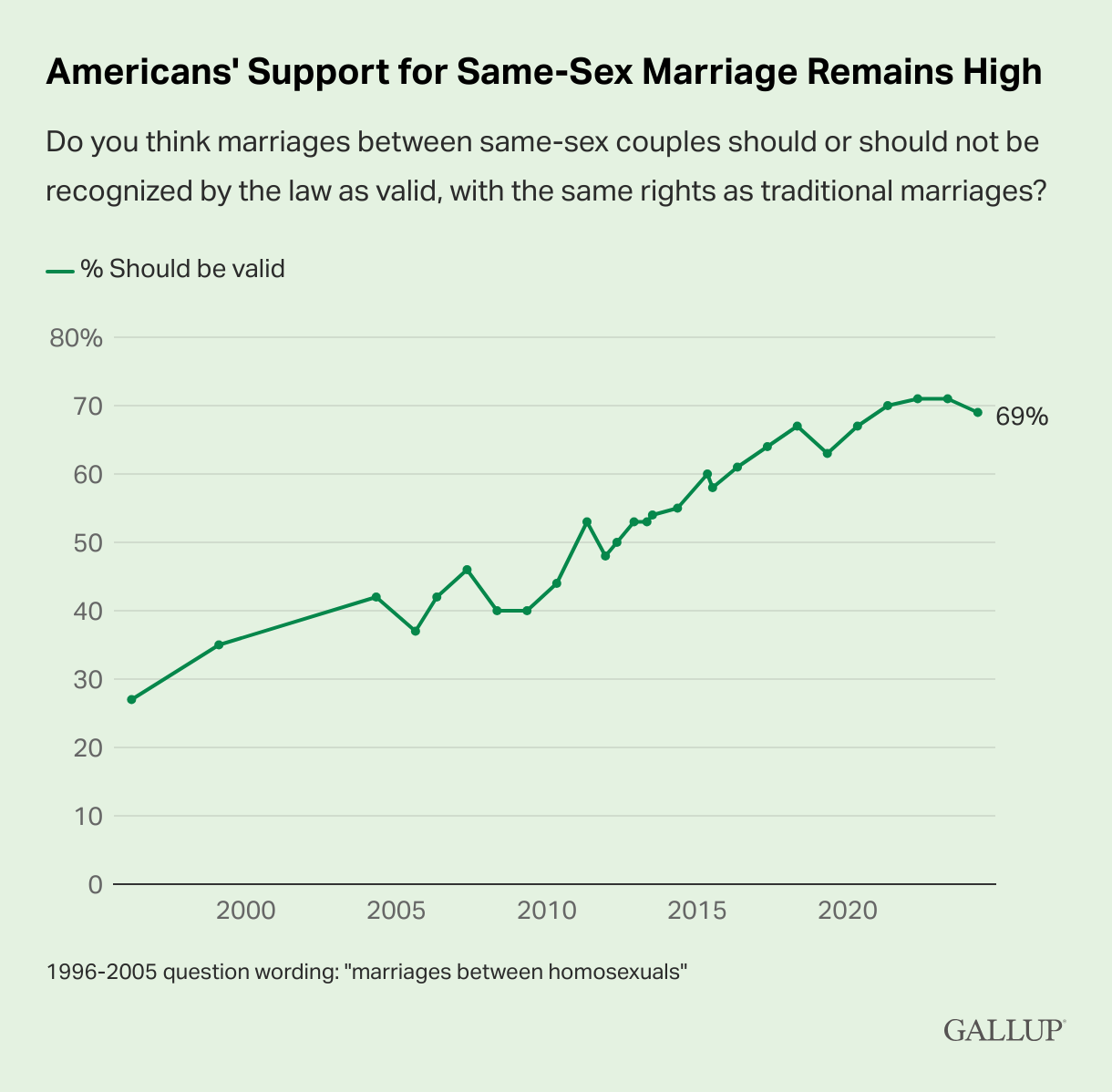

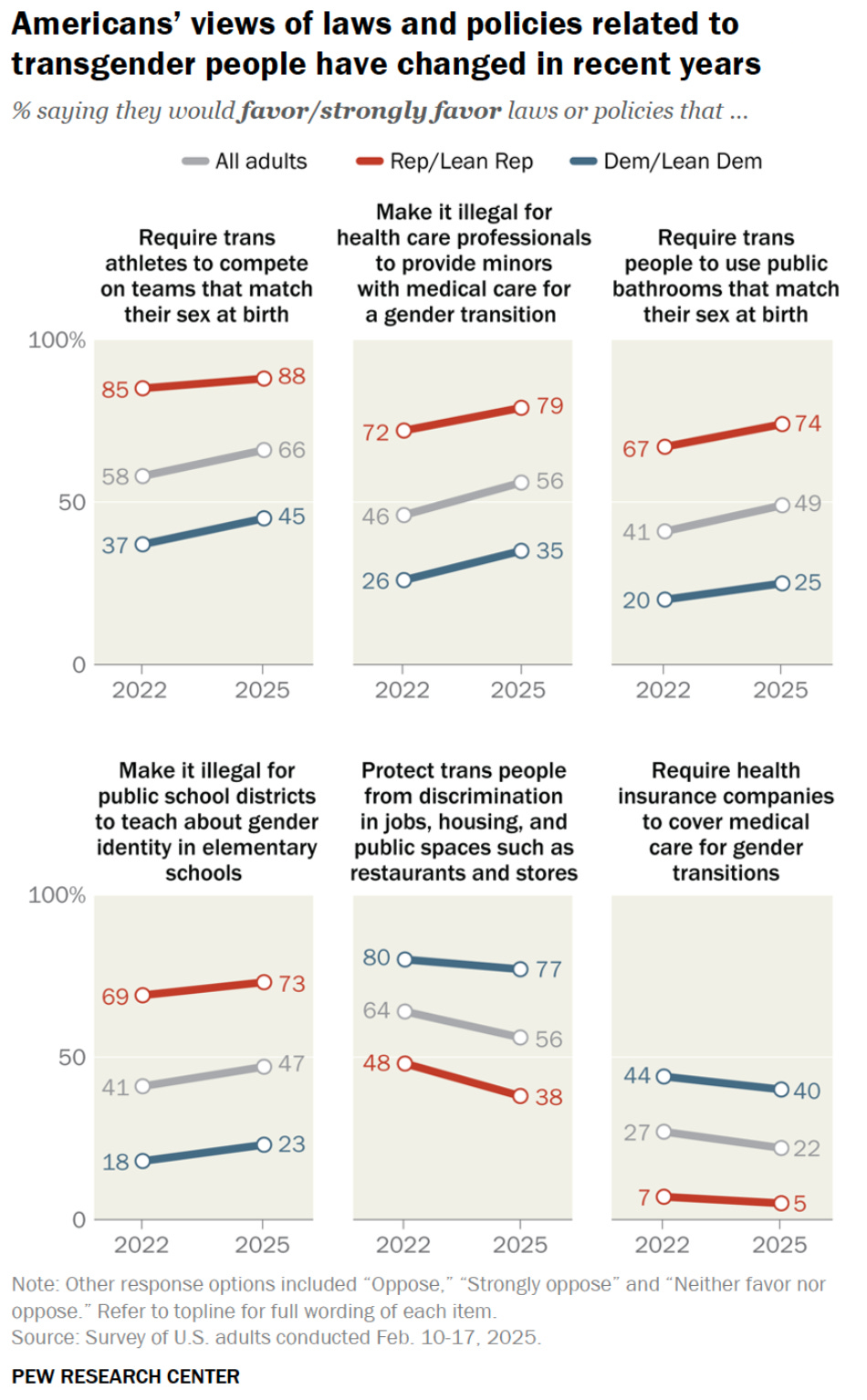

Support for same-sex marriage has plateaued or slightly dipped, but it’s still handily a majority position. By contrast, a growing majority of Americans is opposed to trans women competing in women’s sports, to youth medical transition, and to trans adults using bathrooms that correspond to their gender identity. It’s not just Republicans but Democrats too.

To some degree, this is just a matter of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. The trans movement started building steam just as the US experienced a resurgence of reactionary populism. After the fight against same-sex marriage appeared to be a lost cause, trans issues became a convenient and effective wedge issue. Thus, in an infamous attack ad from the 2024 election, “Kamala was for they/them, Trump is for you.” A May 2025 poll finds that only 41% of Americans approve of Trump’s job as president, while 52% approve of his handling of trans issues.

But the backlash was also exacerbated by tactical errors. It was a mistake to insist that any concern about youth medical transition is transphobic. To habitually take the bait on marginal issues like trans-inclusive sport, particularly at elite levels. To deny that cis women can reasonably desire sex-segregated spaces in locker rooms, shelters, and prisons. To adopt a maximalist politics of pronouns that shames people for honest mistakes. Above all, it was a mistake to seek quick agreement with ideas that run strongly against the grain rather than open dialogue that meets people where they are.

“We’ve lost the art of persuasion,” according to Sarah McBride, the first openly trans member of Congress. “We should be ahead of public opinion, but we have to be within arm’s reach.”

When I’ve talked about this with friends, some suggest that political tactics were irrelevant. Americans are deeply transphobic, they say, and a backlash would have happened anyway. There was no point in being cautious. Better to save as many trans kids as possible before the inevitable crackdown on youth gender-affirming care.

Respectfully, I disagree. It’s not true that anti-trans prejudices are incorrigible. We know that anti-gay prejudices dissolved decades earlier. Approaches that worked then were abandoned now.

To be clear, none of this is about finding someone to blame. It’s about identifying mistakes and learning from them.

I have to admit that some justified trans “asks” are quite onerous. In my view, puberty blockers and hormone therapy are undeniably beneficial for some trans youth, even if early guardrails need to be restored. We need better research on outcomes, yes, but studies aren’t needed to understand that medical interventions offer a brief and vanishing opportunity for trans youth to develop a body that fits their identity and rescues them from lifelong dysphoria and stigma. And yet, anything that threatens children will be a hard sell. Issues that impact trans children will continue to be the site of tragedy.

The path to a responsible form of youth medical care must go through securing more fundamental freedoms. Despite all the backlash, Americans continue to believe that trans people should be protected from discrimination in jobs, housing, and public spaces—by a margin of 40 percentage points. They support including protections for trans people in hate-crime laws by 37 points. The ground is fertile.

As with gay progress, cumulative social and legal acceptance is the best hope, even if it’s not all that one might hope for. It’s “better to move slowly than continue to slide backwards.” We will look back upon these decades with sadness, but we may also celebrate that trans people were finally able to leave the shadows for good.

I support trans people and want them to be able to live their lives. I do my best to respect pronouns, even though it can be easy to slip up at times if I knew them in their previous life (for lack of a better word). Virtually all the trans people I know just want to live their lives in peace.

However, most trans activists are deeply unserious people. They have no concept of strategy, can’t read the room, and are way too maximalist in their demands. I often get annoyed by them and I support their cause (for the most part), so I can’t imagine how those that disagree feel. To me, these tactics probably cost the movement a good 20-30 years due to the backlash, but we will see. There may come a better wedge issue that conservatives can use, which means they’ll likely drop this one.

I’m very skeptical of that paper claiming that higher AIDS incidence at the peak of the pandemic was causal for improved political conditions decades later. I haven’t read the details, but I searched and it does not contain the word “confound”, even though there’s a clear confound in that states with high AIDS incidence at the peak of the pandemic are likely the states with the highest gay population density, which would naturally have some of these effects.

And AIDS was definitely a major setback in gay political progress - in the 1970s, there were a growing number of out celebrities, including people like David Bowie, Elton John, and Mick Jagger, but in the 1980s, many of them went back in the closet. It’s hard to tell how much was backlash, the whole Reagan/Thatcher revolution against the 1970s, and the “disco sucks” movement, and how much came a couple years later with the pandemic starting.