On the first day of Intro to Philosophy, you do the usual stuff: introduce yourself, go over the syllabus, torture the students with icebreakers. It’s tempting to enact another classic trope—to hold forth on what philosophy is.

Some instructors let pedagogical goals shape their answer. They might say that philosophy is careful argumentation or open-minded inquiry into the essential nature of things. These are useful fictions, but there is a correct answer.

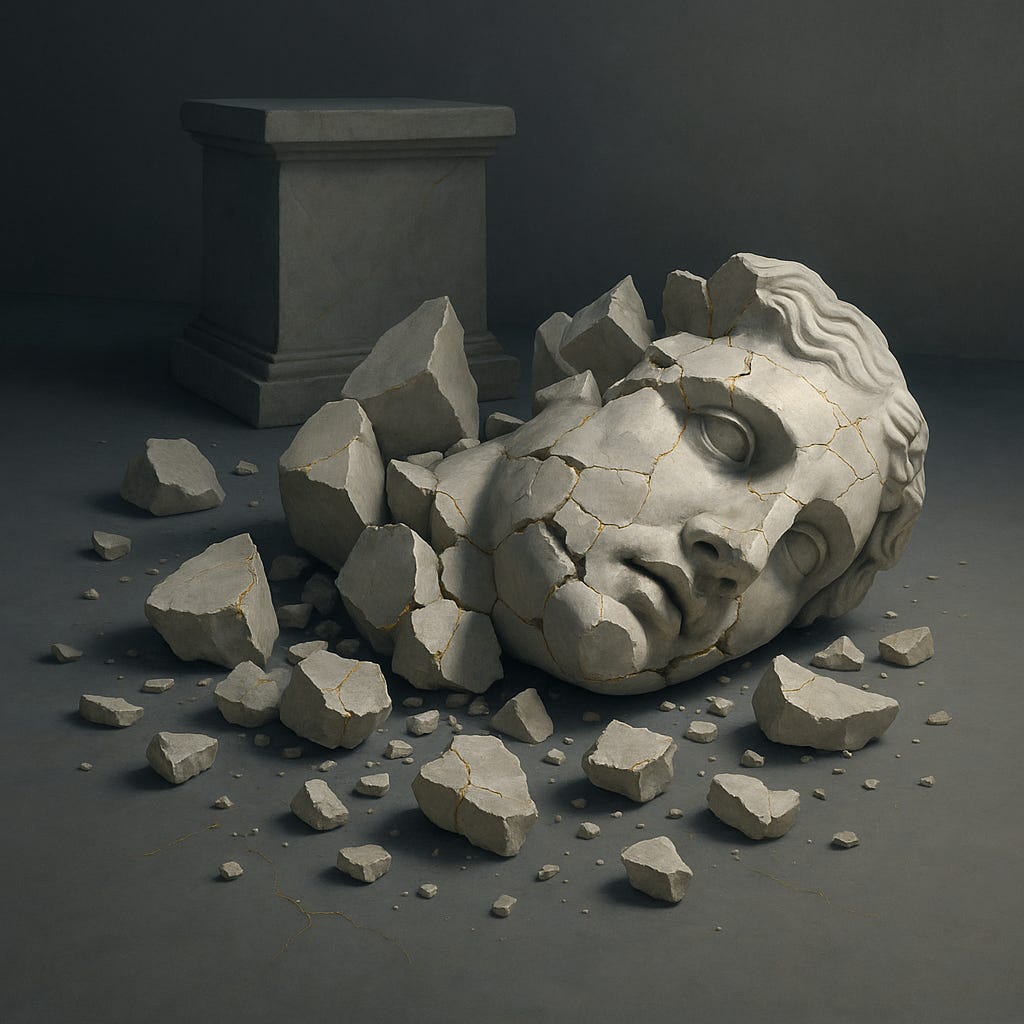

Philosophy is what’s left. It’s the residue.

At one time, philosophy encompassed all formal inquiry except history and a few other fields. As the centuries passed, “natural philosophers” uncovered empirical methods for answering certain questions; entire branches of inquiry then budded off to form their own disciplines, no longer needing to be in intimate conversation with the rest of philosophy. Physics began to escape in the 17th century, psychology in the 19th.

This is an evolutionary answer to “What is philosophy?” rather than a philosophical one. It says nothing about the nature of philosophical inquiry or its distinctive subject matter. Rather, it points to the origin and development of philosophy as a cultural practice. And it suggests that the subdisciplines of philosophy have nothing in common. What remains is just a hodge-podge.

recounts a virtue of the evolutionary view: it explains why there is so little consensus in philosophy, and so little progress. As Bertrand Russell puts it:“[Philosophical] study has not achieved positive results such as have been achieved by other sciences…. This is partly accounted for by the fact that, as soon as definite knowledge concerning any subject becomes possible, this subject ceases to be called philosophy, and becomes a separate science.”

Yet some argue that the evolutionary answer is not only incomplete but points to a complementary yet deeper answer. What’s left, they say, does have something in common—something that explains why it hasn’t budded off. The selection process doesn’t fragment philosophy so much as distill its essence: inquiry into topics that resist empirical scrutiny. In short, philosophy is a priori.

This epistemological view unifies philosophical traditions across the world into a single form of inquiry. It also deepens our understanding of philosophy’s poor track record. Because a priori reasoning is so much weaker than empirical reasoning as a means of acquiring knowledge, philosophers make intellectual progress only by outsourcing empirically knowable questions to those using methods suited to resolve them. Otherwise, we just talk in circles.

Yet the epistemological view faces several problems.

One is that it’s too broad. Math is a priori, if anything is, but it’s not part of philosophy. This problem isn’t insurmountable: philosophy need only be recast as a priori inquiry into not formal but substantive matters. (This is roughly the difference between pure symbols and signs with meaning—or studying the map vs. studying the territory.) Logic is out too, then, though philosophical logic is in.

Another problem is that the epistemological view is simultaneously too narrow. Some parts of philosophy are not strictly a priori—such as empirically-informed projects in philosophy of mind, philosophy of science, and ethics. This problem can also be dispatched so long as the view posits a spectrum rather than a binary, with a priori reasoning at one end and empirical reasoning at the other. Empirically-informed inquiry then occupies the borderlands between philosophy and science. That’s why some such work gets done in philosophy departments, some in science departments.

W. V. O. Quine famously rejected the existence of a priori knowledge, but otherwise this view is his. He thought that philosophy and science are continuous, differing only in how much they relied on abstract vs. empirical reasoning. Since Quine, many philosophers have realized that science can’t rid itself of the a priori (or something like it). After all, what counts as reasons or evidence is often not an empirical matter.

says as much while highlighting the fruitful interaction between philosophy and science. In moral psychology (my old stomping grounds), you can hardly read a paper without stumbling across ideas that originate in moral philosophy—trolley cases, utilitarian reasoning, and more. Thus, the idea that philosophy is a priori is compatible with interdisciplinarity. It’s even compatible with the (correct) view that philosophy should be still more deeply informed by science—that the most fertile soil lies in the borderlands.Yet, for all of that, there remains a deeper problem for the epistemological view: the absence of any illuminating positive account of the a priori. Without that, philosophy is only a nominal category, stripped of any underlying unity. Yes, the a priori is not empirical reasoning in that it doesn’t admit evidence from the senses. But beyond that, what is it?

Kantian inferences about the preconditions of experience are utterly different from inferences based on understanding concepts, and both are equally different from normative reasoning. What could possibly be common to the reasoning underpinning analytic metaphysics, critical theory, transcendental idealism, and so on?

Nothing. It’s just what’s left.

I wonder if the “philosophy is conceptual, not empirical” view is still compatible with empirically-informed projects in philosophy. I think they probably are. Roughly, the idea is that while some philosophical disputes may require empirical input, when that’s all said and done, no additional empirical evidence or data will decisively settle the issue. For instance, moral anti-realists may make empirical assumptions about human psychology, but those empirical claims can’t really settle the dispute between realists and anti-realists. That’s at least the thought—I’m not sure if it works.

I like the idea of thinking about questions that are "left over" or resistant to empiricism. Questions of meaning and value, for example, are not going to be answered by empirical studies. Of course, as Michael suggests below, that does not mean empirical studies are irrelevant to philosophical questions. When it comes to humanistic questions that resist empiricism, philosophy is competing, so to speak, with literature rather than science. We've probably all had the experience of a literary work responding to some "philosophical" question more adequately than philosophy itself. Although on those questions philosophy distinguishes itself with a different standard of rigor and at least a gesture toward universality that is often absent in literature.