Baby Doomers

A review of After the Spike by Dean Spears and Michael Geruso

Many people assume that too many babies are being added to the planet rather than too few, despite decades of evidence to the contrary. A belief in overpopulation has long been a mark of social and environmental consciousness. Perhaps that’s why it’s so sticky.

Then in September 2023, The New York Times published an illustrated essay by Dean Spears, showing the global population peaking within this century and then plunging. More than any previous writing on global population decline, this one cracked the public consciousness.

Less than two years later, Spears and his co-author Michael Geruso have produced After the Spike (Simon & Schuster). The book makes a powerful case that global fertility collapse will spoil humanity’s future, a problem roughly as serious as climate change but vastly more neglected.

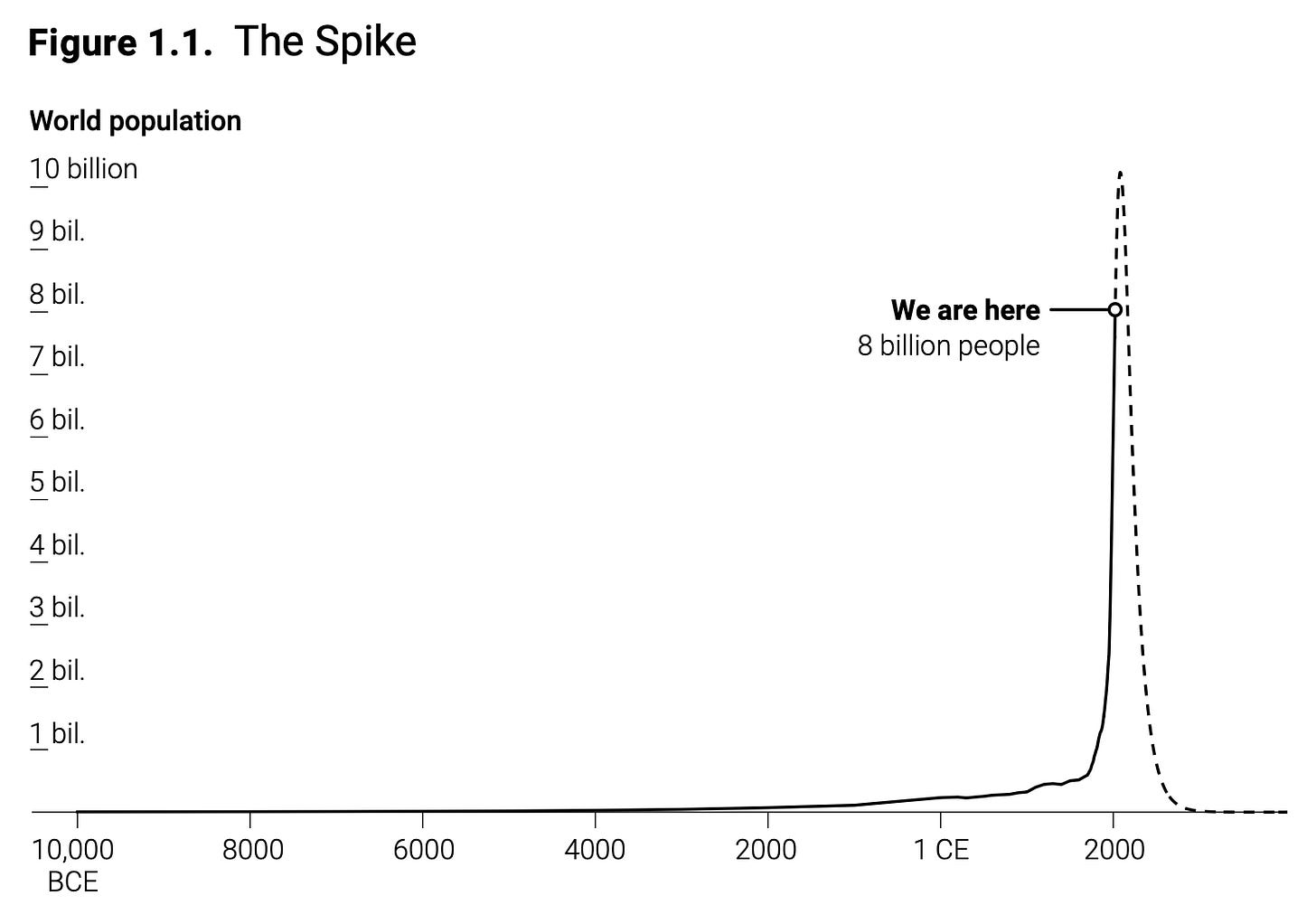

Ten thousand years ago, only five million humans inhabited the planet, “as many people as today live in the Atlanta metro area.” From there, our numbers inched up slowly until the 18th century, when they began to explode, cresting 1 billion in 1800, 2 billion in 1925, 4 billion in 1975, and 8 billion in 2022.

That’s the spike, but what comes after? Like a one-hit wonder, we got really big really fast, but it’ll be all over for us soon:

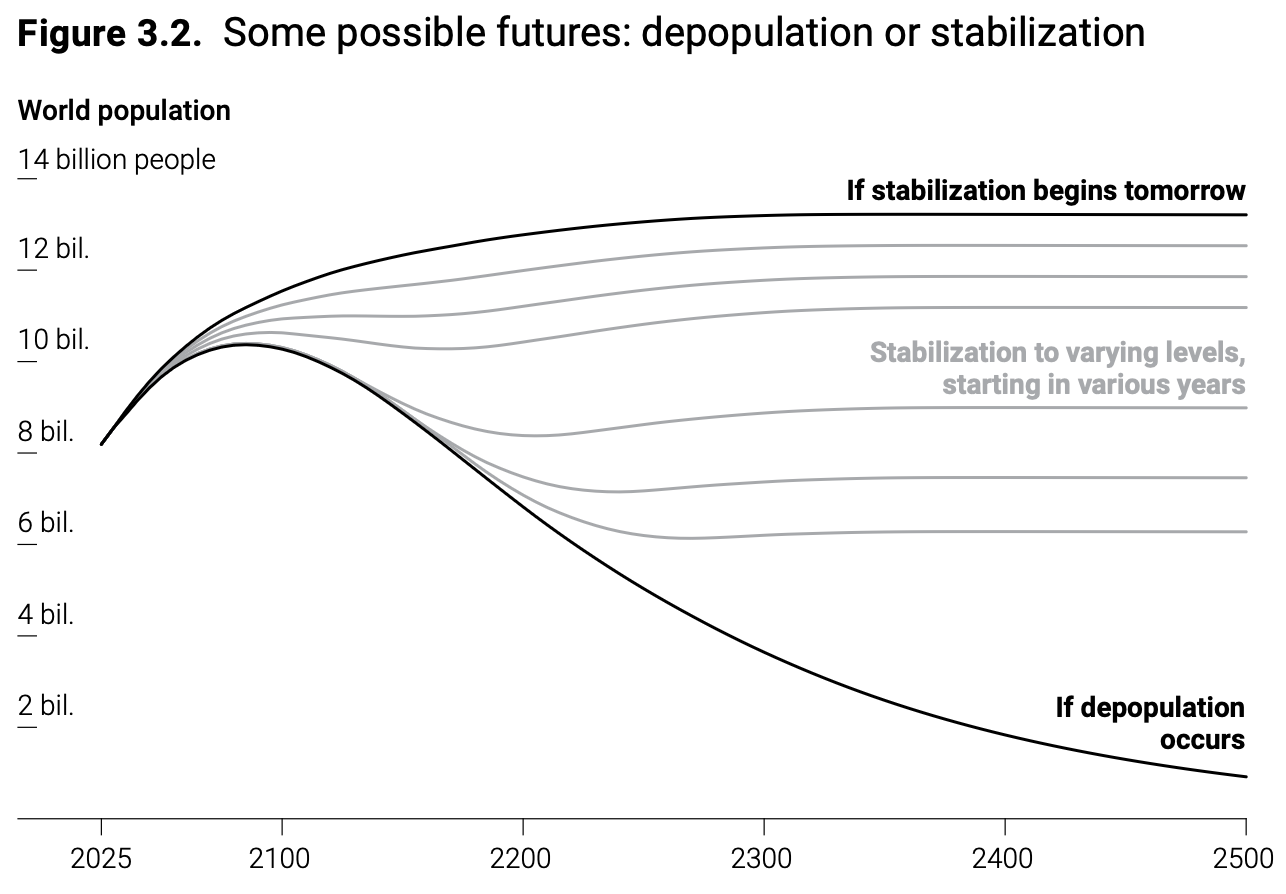

“You, your parents, their parents—any ancestors whose names you know–have been part of a growing population. And now a reversal is on the horizon. Birth rates have been falling everywhere around the world. Soon, the global population will begin to shrink. When it does, it will not spontaneously halt at some smaller, stable size. Unless birth rates then rise and permanently remain higher, each generation will be smaller than the last. That is depopulation.”

Spears and Geruso tell us that more children were born in 2012 (146 million) than in any prior year—and perhaps also any subsequent year. Across our species’ entire history, there have been 120 billion humans. If we remain on our present course, “then humanity’s story would be mostly written. About four-fifths written, in fact.” Only about 30 billion births would remain—ever.

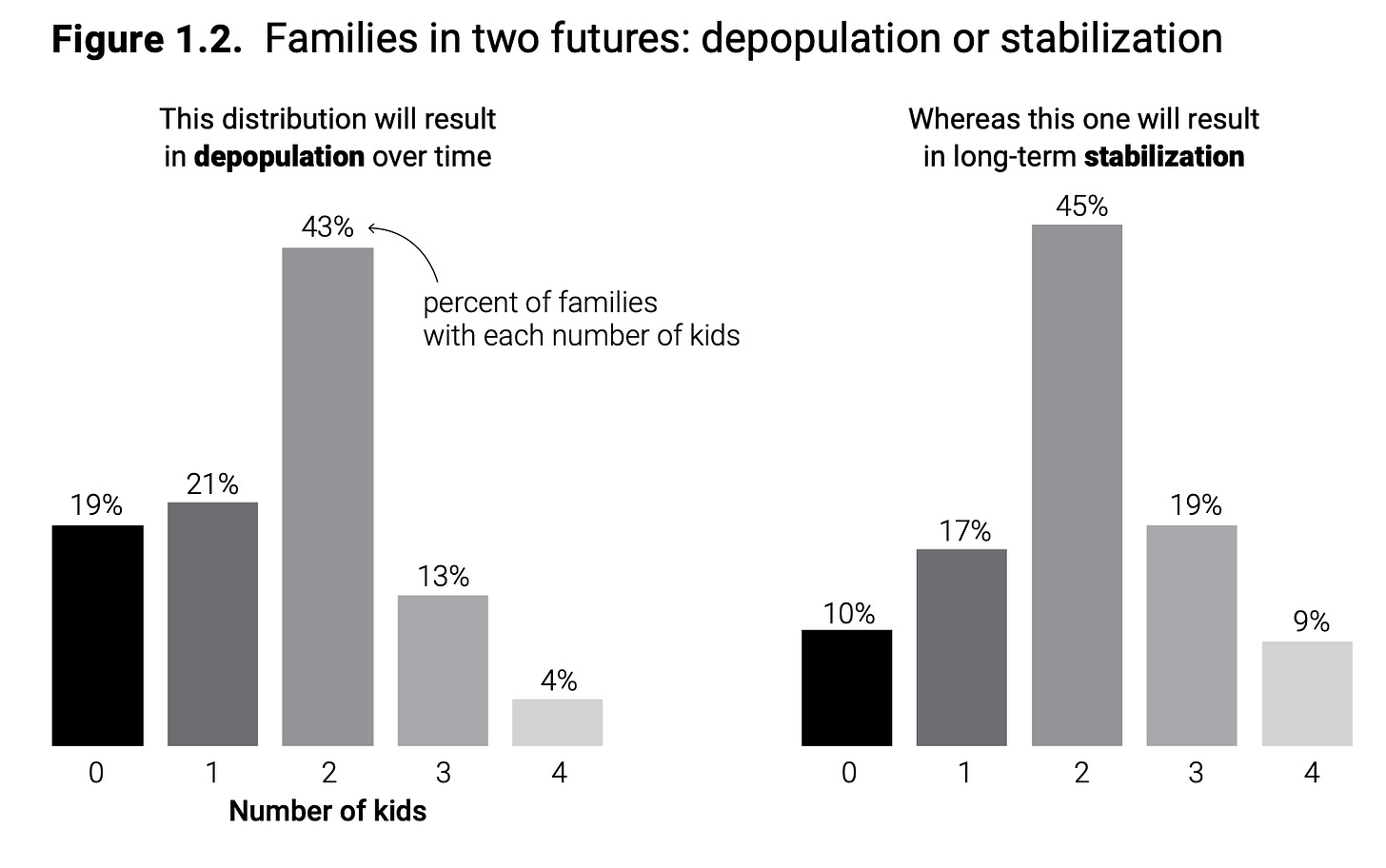

Why? Population growth is exponential, but so is population decay. As long as women have fewer than two children on average, depopulation is coming. It doesn’t matter what the birth rate is precisely, so long as it’s under that magic number. Nor does it matter if life expectancy surges—there will still be fewer and fewer humans born to replace those who (eventually) die.

After the spike comes the fall.

Much of After the Spike is taken up with dispelling misconceptions, according to which depopulation is desirable or easily mitigated.

What’s so bad about a planet with only 4 billion humans on it? Or 1 billion? That’s plenty. Perhaps, but depopulation won’t stop there. If the global fertility rate drops below two, our numbers will keep shrinking. No mechanism will automatically kick in to level them out.

Just let more immigrants in. Wealthy nations should welcome more immigrants, but depopulation is coming for the entire globe. The only type of migration that would reverse that trend is interplanetary.

Depopulation is necessary since we’re running out of food and other resources. In fact, food production has risen faster than population. Famines aren’t natural disasters but political failures—“driven by armed conflict…[or] the terrible choices of regimes in power,” diverting available food from those who need it. Other resources have only become cheaper and more plentiful over time.

The future is a hellscape. There’s no sense bringing more humans into it. No one is invulnerable to tragedy, but by every objective measure—health, wealth, longevity, education—human lives have improved dramatically. The belief that climate change will make future generations poorer is an example of what Joseph Heath calls highbrow misinformation. Evidence shows only that climate change will cause global economic output to increase more slowly than it would otherwise; it will still grow.

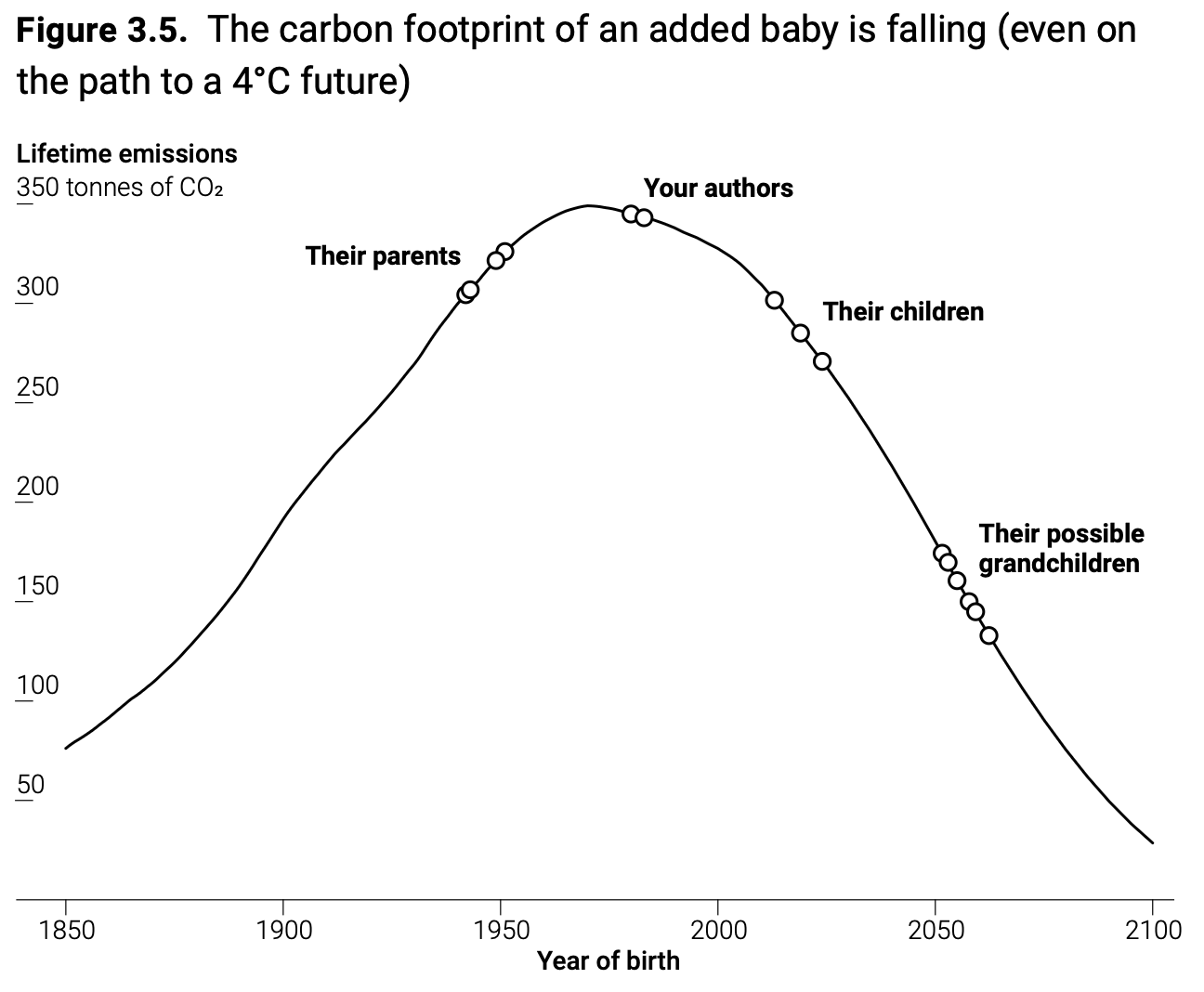

The most common challenge Spears and Geruso face also relates to climate change—not what future people will suffer but what they’ll wreak. Fewer people, fewer emissions. Yet depopulation will come far too late to thwart climate change. We must decarbonize as quickly as possible—and whether we decarbonize will swamp the effect of population size on emissions. Changes to birth rates will have a minuscule impact on population size in this timeframe. (This is a verbal rendering of their argument, but Spears and Geruso have the math to prove it, along with a new NBER working paper with colleagues.) Carbon footprints shrank in the past, and even given pessimistic projections, they’ll continue shrinking in the future.

So much for reasons to welcome depopulation. Why should we fear it? Simply put: More people, more ideas, more progress. This is the central argument of the book.

It’s not physical capital but ideas that drive progress. Ideas can be transferred without loss. As Jefferson said, “He who lights his taper at mine receives light without darkening me.” The more people around, the more useful ideas are generated.

There’s more to this theory than the authors articulate. It’s not just that in a more populous world, more people are making more discoveries—minds embedded in larger social networks are also more innovative, as Joseph Henrich and others argue. They can download more concepts and tools. They’re also more likely to find themselves in institutions that cultivate superior epistemic norms and habits.

It’s no coincidence that the eruption of technological innovation and consequent progress over the last two centuries followed humanity’s recent population growth. Think about electricity, germ theory, vaccines, and computing technology. Without a large network of innovative minds, this progress could come to a halt.

In one of the most memorable passages from the book, Spears and Geruso capture why the world isn’t zero-sum: “Your neighbors are not eating your pie slice. They’re the reason someone is baking.” Greater social demand incentivizes production by overcoming fixed costs. It also incentivizes innovation and enables specialization. This is the value of economies of scale—why people pay a premium to live in cities.

With fewer people on Earth, total economic output will be smaller. We may not be able to afford the costs of cleaning up excess atmospheric carbon even if we manage to stop emitting, nor the costs of foiling cataclysmic disasters like rogue asteroids or deadly pandemics. “The end could be some catastrophe that a larger population might have survived but a smaller population couldn’t.”

Depopulation is not just smaller numbers on a chart—it’s fewer living, breathing humans with unique and valuable personalities. A world with more good lives in it is better. It doesn’t follow that any particular means of achieving this end is justified—certainly not curtailing reproductive freedom. And adding more people won’t reduce the quality of other lives. (Hold your repugnance.) Just the opposite: more people, more quality.

The global population won’t begin to decline for decades, but it’s wise to begin thinking about solutions now, just like we wisely began thinking about climate change many decades ago. How can we nudge family size just a little bit upwards without violating anyone’s rights?

No acceptable policy will coerce women into having children. As I said on a recent NPR podcast, and as Spears and Geruso repeatedly affirm, reproductive autonomy should be treated as a “fixed point” in an exploration of effective policies.

Plus, averting depopulation does not mean winding back the clock on 100 years of rising gender equality. In the US and other countries, birth rates remained stable while women became more liberated. As the authors say, acceptable and effective solutions will come through people choosing to have more children. In the US and many other countries, intended fertility exceeds 2 children per woman; the goal is just to help people have as many offspring as they desire. My essay last year in The New York Times argues that one can and should be a progressive pronatalist.

So what do we do? Spears and Geruso are mainly negative, identifying which policies won’t be effective.

Governments have no straightforward incentive to increase birth rates. Babies take two or three decades to become contributing members of society (sometimes longer, if they go to grad school), so any economic benefits will accrue only decades after a politician’s term in office. Governments also can’t coerce citizens to reproduce even if they wanted to. Authoritarian leaders have tried and failed. This means, again, that “choice is what will matter in the long run.”

American progressives love to imagine that all our solutions can be found by imitating Scandinavian policies, in this case by subsidizing maternal health care, child care, and parental leave. Only one problem: these policies don’t work. Sweden’s fertility rate is the same as the US’s. Nor do straight cash subsidies, at least not on any scale that is currently within the bounds of political imaginations.

Spears and Geruso also discount technological solutions like artificial wombs. People wouldn’t decide to conceive more children even if pregnancy were less costly. The opportunity costs of raising children are too high.

After the Spike is elegantly written but not a feel-good story. Its goal is to persuade readers that collapsing fertility threatens to spoil humanity’s future—that depopulation is a global problem on the order of anthropogenic climate change. Despite this, it seems to me that the authors underestimate its severity.

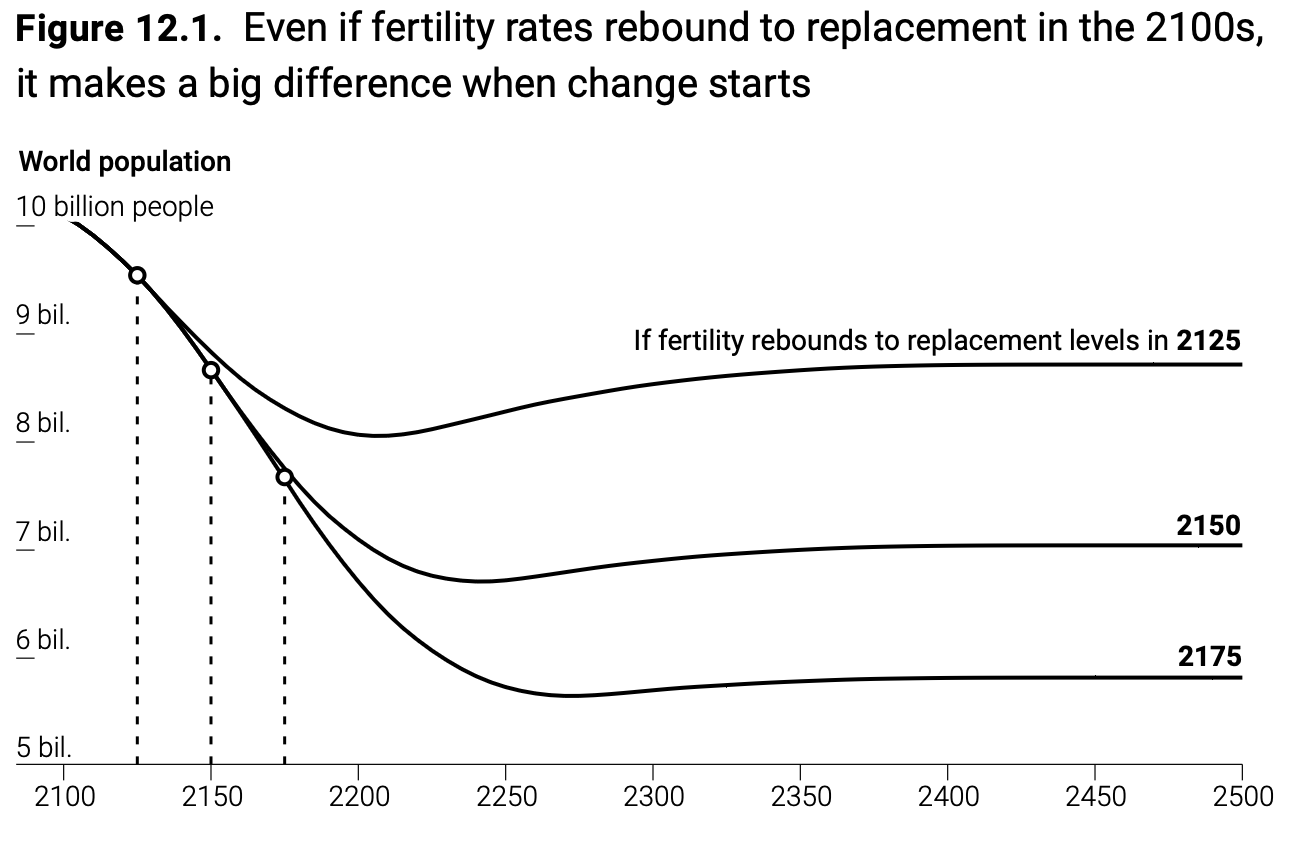

At one point, Spears and Geruso suggest that humanity will shrink to 2 billion people three hundred years from now. Attentive readers know that this isn’t a stable equilibrium. Humanity will continue to shrink. Still, 2 billion isn’t that small—identical to our sum total one hundred years ago—and we’ve got hundreds of years still ahead of us to turn the ship.

As I argue elsewhere, however, the problem isn’t just a smaller population but an aging one. Fertility collapse will lead to a distorted population structure, with fewer and fewer young people.

Spears and Geruso seem to anticipate this problem:

“The most common worry that one hears today about the economics of depopulation is that too few workers or too many retirees would foul up government budgets or the labor force. Maybe so. Or maybe our societies can solve these problems without stabilizing the population. Yes, the U.S. old-age dependency ratio (the number of people sixty-five and over relative to the number of people twenty-five to sixty-four) will double over the next seventy-five years. But it has already doubled over the past seventy-five years, and that doubling hasn’t brought catastrophe.”

I’m less sanguine. It’s not just social security that relies on the number of workers—it’s also education, health care, infrastructure, public safety, and welfare. And to fund these programs, there’s only so much you can squeeze out of workers. Ultimately, though, I agree that this is a problem for “think tanks” and “wonky discourse.” The deeper problem is that a world with fewer and fewer young people has other costs, and that these are far more resistant to policy solutions.

One cost strikes at the very heart of the book. Progress depends on the generation of new ideas, but this itself depends on not only population size but also population structure. Young people drive innovation; as they vanish, progress will wither.

That’s not all:

“Social progress [also] depends on young people rejecting prevailing bigotry and replacing older generations…. If the proportion of young people declines, so will our moral and political values. You think we live in a decaying gerontocracy now? Just wait.

The impact on creative activity will be no less profound. Young people have always been the main source of art, fashion, music, literature, and film. As their numbers diminish, the future will become a cultural wasteland.”

More people, more ideas, more progress—yes. But to evaluate humanity’s future, we shouldn’t focus exclusively on scientific and technological ideas, ignoring moral and creative ones. Moreover, young people do more than their fair share of idea generation. Fertility collapse heralds “the gradual dissipation of this vital social force.”

All the more reason to achieve replacement, sooner rather than later.

By the end of After the Spike, readers may feel persuaded but not assured. Spears and Geruso admit that they don’t know how to avert depopulation. They would, however, like to “start a conversation.” This is somewhat underwhelming. The authors aren’t “doomers,” but at times their book encourages a pessimistic outlook.

I think there are more grounds for hope than Spears and Geruso allow. They grant that subsidies may have small effects. France’s generous tax breaks for parents also seem to marginally increase fertility. Individually, any given policy has very small effects at best, but what we need is an arsenal of interventions that together can boost fertility rates by 0.5 or so.

And we’re not limited to subsidizing pregnancy and child care. We should also pursue policies that make workplaces more child-friendly, reduce gendered divisions of household labor, increase housing availability, and promote new models of cooperative parenting. New reproductive technologies—artificial wombs and the like—are also more promising than Spears and Geruso suggest. Surely pregnancy comprises part of the cost of parenting. And other new innovations—like robot nannies and AI tutors—can bring down the costs of post-pregnancy childrearing.

Cultural changes may be needed too, even if they’re hard to control via policy. In a perceptive review of After the Spike,

argues that we should make parenting higher-status. Progressives have somehow convinced themselves that childlessness is not just permissible (true) but admirable (false)—partly due to misconceptions related to climate change. Progressive culture needs to be fixed in many ways, but one is to create a healthier perspective on parenting and the future of humanity.It’s a good bet that AI will be sufficiently impactful so as to expand our options in ways that we can’t yet grasp. Optimists hope that it will compensate for the dearth of natural-born ideas; pessimists may worry that it will allow tomorrow’s authoritarians to exercise more coercive control over their citizens’ reproductive choices. But we should be much more confident that powerful AI will provide some purchase on depopulation than we are about its exact use.

Just as with climate change, our best hope is to harness technology rather than only work the levers of social policy. Spears and Geruso say they “cannot rule out the possibility” of AI mitigating the harms of depopulation, nor rule it in. Sure. But if their recommendation ultimately is that we have to think more about the problem, then AI should be central to that thinking.

Looking forward, we also need a more concrete plan than “think hard.” I suggest a two-track approach. First, we should immediately implement interventions that are independently worthwhile, like subsidies and tax breaks. These would relieve social and financial burdens on parents, especially mothers, even if they had zero effect on fertility. And second, we should invest in technical and ethical R&D on more ambitious approaches—including radical forms of assisted reproductive technology—preparing ourselves for future implementation if need builds and political will accumulates.

Fertility decline is such a predictable consequence of economic development, that it’s hard to envision an alternative to depopulation. But technology introduces new possibilities and more uncertainty.

After the spike? Maybe there’s a lot more to our story.

Are they advocating for constant population growth, or merely aiming for stabilization? To the extent that the arguments you discuss here suggest that fewer people is a bad thing for humanity, then the extension of this would be that mere stabilization isn't desirable either, right? To stabilize rather than increase the birth rate would also mean fewer living, breathing humans with unique personalities, and a slow-down in technological progress.

My only fear with this kind of argument is that it presumes not only that progress is a good thing (agreed), but that the rate of progress should also be accelerating.

Moral progress (whatever that means), sure, that would be great to accelerate. But technological progress? I am not so sure. When it comes to AI and related tech, would stabilizing the pace of progress be so bad?

Increasing the pace of progress may make it less likely we stick the landing with these increasingly societally destabilizing technologies. Obviously this is a complicated issue (increased tech = better health care, better solutions to many problems), but simply assuming increasing the *pace of progress* is an unadulterated good seems like a stretch.

Anyways, thanks for the great review. Definitely going to check this one out.

Humanity is smart enough to produce this crisis and they are sure to be smart enough to solve it. When has this been ever not the truth 😎